Disrespect, disenfranchisement and disinheritance of workers—of whatever race, color or creed—produces “a fertile environment” for hate and “fascist ideology.”

So said Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in a speech to the AFL-CIO convention in 1961, and that’s still true today, says AFL-CIO Secretary-Treasurer Fred Redmond.

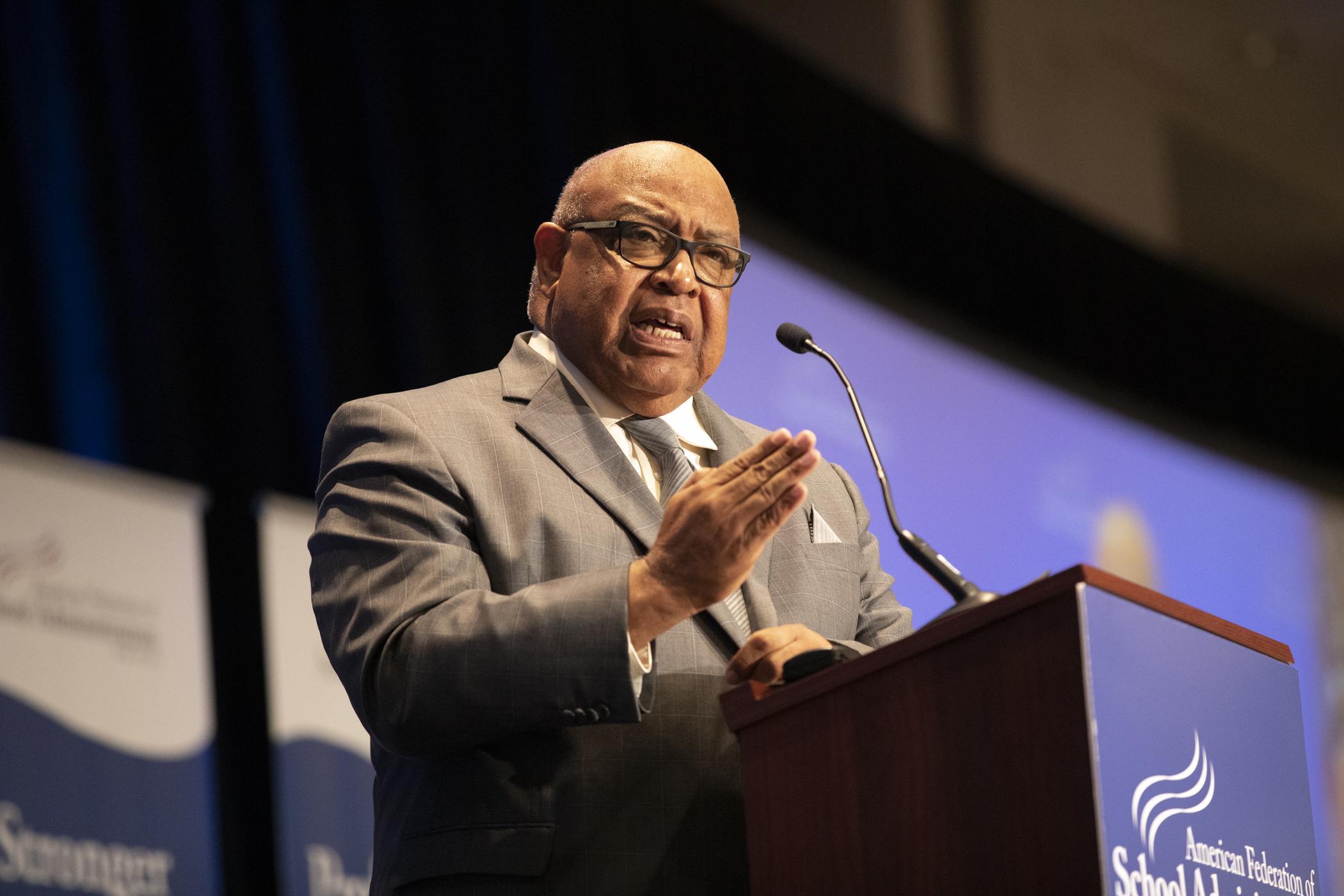

Which is a big reason, Redmond told the federation’s annual Martin Luther King Jr. commemorative conference held last month, that organized labor and the civil rights movement should have united then—labor was reluctant—and must stay united today.

Redmond, who chaired the conference, followed his leadership partner, AFL-CIO President Liz Shuler, to the podium. Both were tough on democracy’s foes, though neither specifically identified them by political party or by name. They didn’t need to.

“Over the past few years we’ve seen the rise of misinformation, of political polarization dividing our communities, the rise in attacks on our basic freedoms like the right to vote and organize a union, and attacks on our democracy itself,” said Shuler.

“As a labor movement, we have to respond. We know how to use our voices to fight back against those in power who want to weaken and diminish us," she said. "We know how to leverage the power of collective action. Speaking together, in one clear voice, demanding change, is one of the best hopes our nation has not only for a continuing but also a thriving democracy.”

Redmond hit the same points in his keynote address to the annual conference, which this year made defense of democracy one of its top themes. It’s title: “Claiming Our Power, Protecting Our Democracy.” But he reminded listeners the labor-civil rights alliance didn’t always exist.

“Dr. King had made his connection to our movement known time and time again. In fact, when he addressed the AFL-CIO convention in Florida two years prior, he said the two most effective voices for social and economic justice are the labor movement and the civil rights movement,” Redmond explained. “Dr. King made an appeal for our two movements to join together to lift up the concerns of workers and those who have been disrespected, disinherited, disenfranchised in our communities.“

But in a difference between then and now, Redmond recalled Dr. King’s “call went unanswered.” And when the civil rights leader approached then-AFL-CIO President George Meany for labor to help fund the now-fabled 1963 March on Washington that August, Meany turned him down.

UAW President Walter Reuther stepped forward with the needed dollars, though—and became the only White leader to address that march’s crowd. He declared to Whites they must be part of the movement for political and economic justice, too, Shuler said.

“Let us answer that call” by Dr. King “today,” Redmond urged. “Because his concerns remain. Workers are still being disrespected. Workers are still being disinherited. Workers are still being disenfranchised.

“These issues don’t just affect their lives in the workplace. These concerns deepen inequality everywhere, in every aspect of life," he said. "And places where workers don’t feel valued or respected are a fertile environment for misinformation and disinformation to seed hate and fascist ideology.

“And when those hateful feelings are fomented, they put our very democracy at risk. They lead to policies of voter suppression designed to take away the very tools that give us a voice in who governs us.

“Dr. King knew that. That’s why he knew it would take both movements—the labor and civil rights movements—working as one to create true opportunity, true equality, true democracy. He knew a good union job protected workers from discrimination, and that union workers had higher wages, health care, safer jobs."

Redmond continued: “He knew a good union job was often the first step in generating wealth and creating economic power. It made the difference for folks who had little opportunity. It allowed them to buy a home and save for retirement and give their kids a start with a solid footing. One by one, those jobs supported and lifted up communities all across the country.

“A good union job was often the first step in reversing an unequal system that has caused generations of damage. I say ‘the first step,’ because that economic power also translated into political power, at the ballot box and on Capitol Hill. It gave people a voice at work and in our nation. That’s why Dr. King worked so hard to bring together” the two movements.

In the days after Shuler’s and Redmond’s speeches, delegates brainstormed how to strengthen the labor-civil rights alliance, forge alliances with other progressive groups and tackle causes ranging from implementing organizing to battling structural racism to campaigning for equal rights and eventual full citizenship for undocumented people.

But they also realized that while they’re committed to action, they must bring their union colleagues along.

“I’m going to have to think about how to get more people involved to change these policies” that oppress workers and people of color, said Andre Francis, secretary-treasurer of Steelworkers Local 13-243—an oil refinery workers local—in Beaumont, Texas, after attending a small-group breakout session on how to battle the threat to democracy.

“I’ve got to get them educated on who, what, when, where and why” labor and civil rights members and activists support each other—and do so all year round, not just at King conferences or in election campaigns.

“I’m learning a lot about inequality and politics, especially as it involves my members,” he said. As for candidates, Francis added, “We have to be aware of their agendas.”